“New Language of Ancient Architecture,” was the first and largest project I worked on during my placement. It was in Jincheng, which is not a developed city, but it is known for historic architecture and deep cultural heritage. The exhibition ran 30/09/2025–31/12/2025 and was a collaboration between our company and the Jincheng municipal government to promote local architectural culture and support the local arts.

The exhibition comprised two parts: one is the group show Cosmic Alignment, featuring ten Chinese and international artists; the other is the site-specific project The Eightieth Day.

Exhibition 1 — Cosmic Alignment

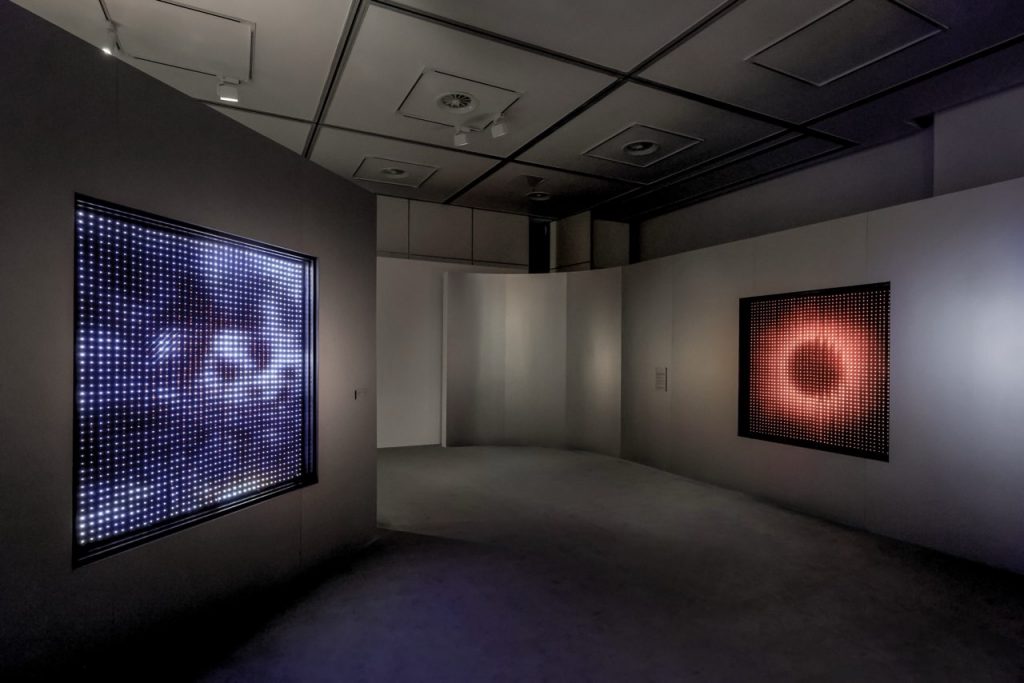

The gallery footprint was modest, but the spatial design was smart: tailored niches for works across very different media and styles, unified by a deep blue–silver palette that sustained a cosmological atmosphere.

Concept

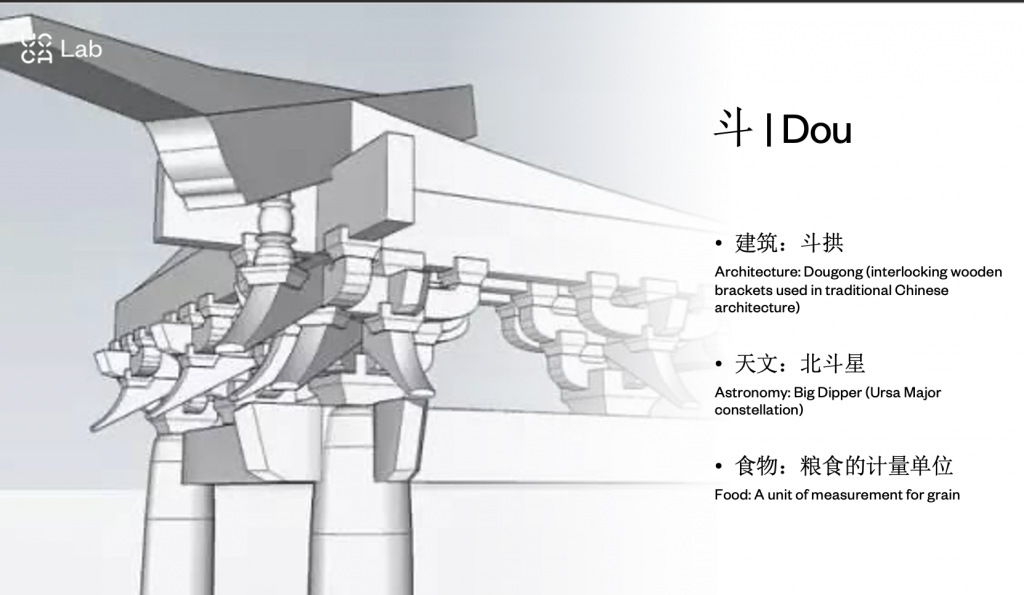

“Cosmic Alignment” grows from the Chinese character “斗 (dou)”, bridging architecture, astronomy, and agriculture.

This ancient unit of measurement interconnected three pivotal technologies—mechanics, astronomy, and numerology. I think this concept is extremely brilliant!The exhibition explores ancient Chinese cosmology through material and technological lenses, embodying the unity of space and time, an infinite universe, and the relationship between humans and the cosmos.

Selected works

Zhao Xiaoxiao, Cloud Atlas, 2022, aluminum, electronic components, carbon fiber rods, 160 × 300 × 160 cm

This is a kinetic installation. It uses sensors to collect real-time air-quality data and converts it into changes of form, color, and sound within the mechanism, making otherwise invisible atmospheric conditions perceptible. Like a “translator,” it lets viewers sense environmental change through sight and sound, drawing attention to the interplay between human activity and the state of the air.

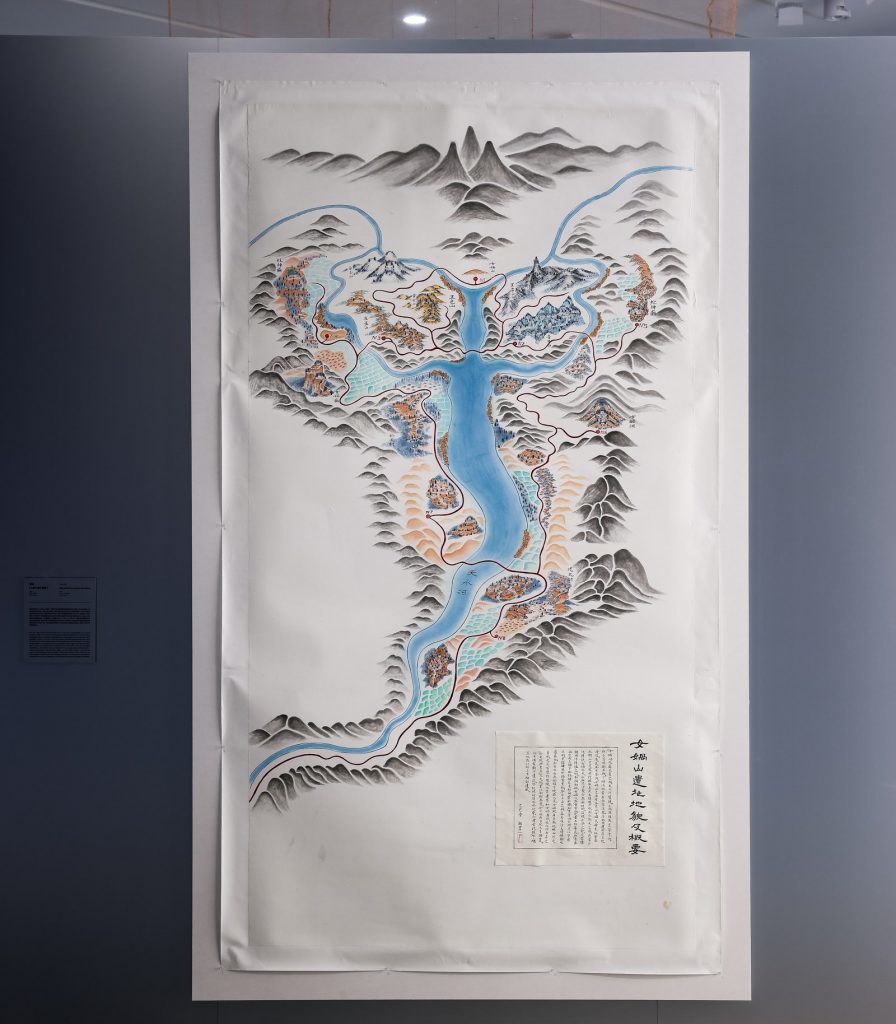

Xie Qun, Map of the Nuwa Mountain Ruins, 2025, ink on xuan paper, 240 × 123 cm

Inspired by Chinese myth of Nuwa patching the sky, the serpent-bodied figure is transformed into the counter-form of earth veins and mountains, symbolizing unity between human and natural form. The work situates myth within concrete spaces and practices, combining material-culture research with anthropological imagination.

I have been reading the Classic of Mountains and Seas and am drawn to the ties between mythical creatures and their geographies; this piece turns myth into a legible spatial and productive reality.

Tong Kunniao, Guardians, 2025, corrugated cardboard, paint, 300 × 300 × 300 cm

Using discarded cardboard, the artist reconstructs the dougong structure (interlocking wooden brackets) from traditional architecture and paints the Four Symbols(the protection of the four directions). Standing before it, I felt surrounded by stars and ancient temples, sensing the link between cosmos and architecture, faith and belief. I can feel the depth of ancient imagination about the universe.

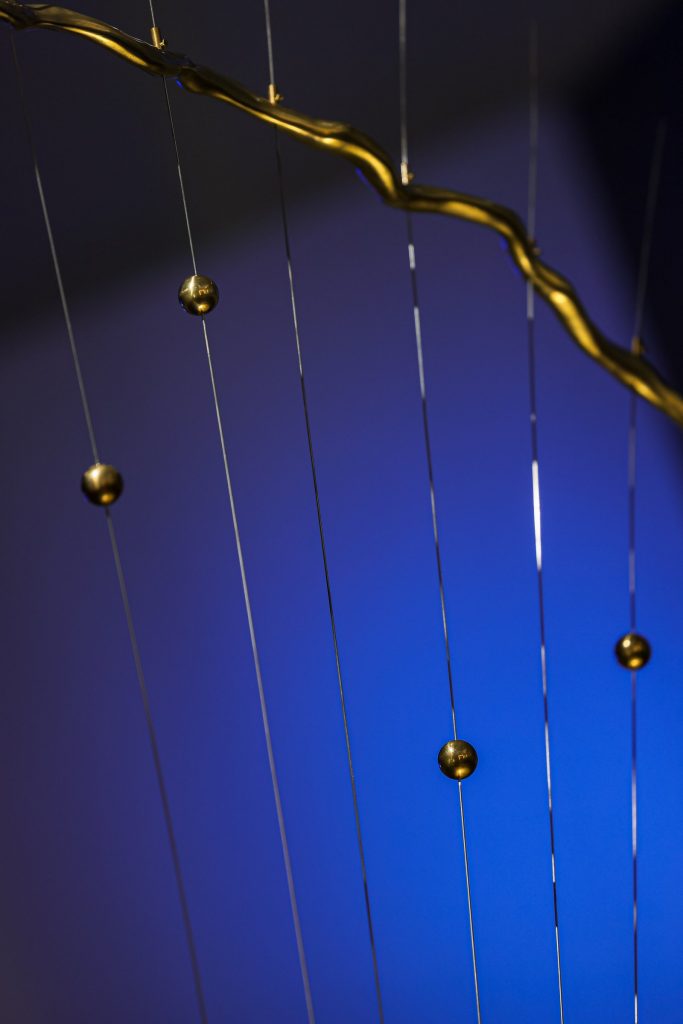

Chen Zhe, Quadrant, 2022–2023, brass, aluminum, stainless-steel wire, φ300 × 182 cm

The work draws on the ancient practice of “measuring with the body”—telling time by observing one’s shadow in sunlight. Later generations invented astronomical instruments to refine this temporal order. The artist suggests humans have never been separate from nature; the cosmos is apprehended through the body, expressing Chinese philosophy about“the unity of heaven and humanity”.

Gabriel Lester, Small People, Big Shadows, 2024, conveyor, tree models, figurines, 45 × 50 × 46 cm

Two light-based works continue Lester’s long-term inquiry into narrative, motion, spatiotemporal perception. Figures and objects travel on a conveyor while constant light witnesses their passage. It reminded me of a famous accent Chinese poem sentence:

“People today do not see the moon of old,

yet this moon once shone on people of the past.”

The light behind is like the moon that remains constant, quietly witnessing change and the passage of time.

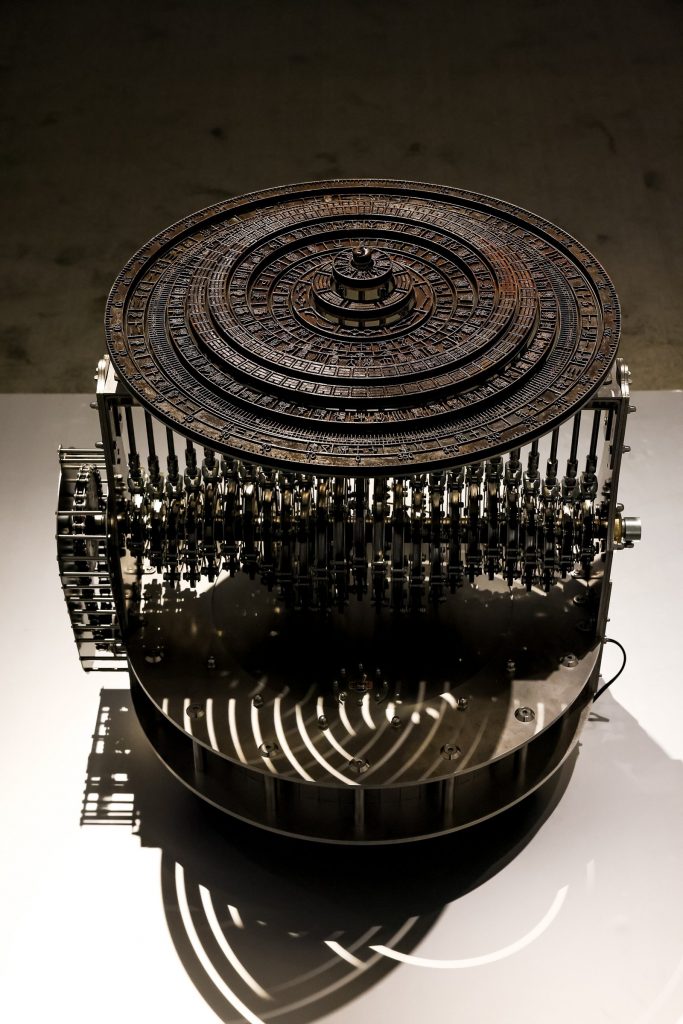

Nie Shichang, Droplet Oscillator, 2025, mixed metals (iron, stainless steel, copper), 90 × 70 × 80 cm

Based on calendar systems derived from sky-watching and agricultural time, the work embeds yin-yang lunisolar principles in concentric rings. It is Merging natural ripple patterns with compass-like forms, a mechanical transmission simulates wave dynamics. As the device runs, rings inscribed with celestial symbols rise and overlap like waves, suggesting a link between subtle variation and grand cosmic order and inviting reflection on natural laws within traditional Chinese cosmology.

Emily Cheng, Cassandra, 2023, Flashe on canvas, 28 × 36 cm

Cheng explores the spirituality of painting and cosmological philosophy, constructing visions that link inner spirit and universe through abstraction. Combining Daoist talismans, scientific illustration, and prehistoric rock art, she dissolves boundaries between inner/outer, individual/collective, past/present.

Exhibition 2 — The Eightieth Day

This large-space installation draws on the myth of Nuwa patching the sky. Using raw cowhide, natural stone, and mixed media with instrumental performance, it focuses on the moment just before cosmic order is restored.

I appreciate this immersive format that invites reflection.Walking through, I felt suspended between destruction and repair, chaos and order—as if back before the birth of civilization, about to witness the shift from turmoil to structure. It prompted three questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? Where am I going?

However, as an animal-protection advocate, the material of this work – cowhide – made me into deep reflection. I understand cowhide is a by-product of beef production. It is common in everyday life such as car interiors, bags, where its properties are functionally used. However, in this exhibition, over 200 sheets of dried cowhide were simply suspended in the space, without any real use of their material properties. What will happen to them after the show?Stored away or discarded?

To me, cowhide is not strictly irreplaceable in this context. While Damien Hirst’s work is controversial, His works expose how the living often face death with indifference, even turning it into a spectacle. However, The Eightieth Day explores the dawn of civilization; if the aim is to evoke a primordial atmosphere, fabric or recycled, low-impact materials could achieve a similar effect. More broadly, creative practice should move beyond a human-centered default, ask what “nature” or non-human creature would say, and keep sustainability in view.

A Setback — and What It Taught Me

Beyond this, the project also left me with another important lesson. Our original plan was more ambitious: beyond the exhibition, we scheduled a week-long outdoor stage performance over holiday, designed by famous architect Ma Yansong and directed by Liu Chang, blending contemporary theatre with local traditional opera—a genuinely inventive program. The entire team believed in its artistic merit. Yet one week before opening, the mayor and the police department canceled it, even though rehearsals and stage construction were complete.

From the mayor’s perspective, parts of the work were too avant-garde and dark for an official, government-partnered event. The police cited practical concerns: hundreds of spectators in an open square, insufficient parking, and potential crowd-safety risks. This was my first real lesson that artistic creation is not absolutely “free.” The same artwork conveys different meanings when viewed from the perspectives of different social roles. Mature projects must balance multiple viewpoints; while pursuing artistic ideals, we must fully account for real world conditions and social context.

Conclusion

This project gave me more than new sources and ideas for my research: it deepened my understanding that artistic work must weigh environmental responsibility and communication to different role, alongside concept and form. I’m certain the experience will stay with me and inform my future practice.

Leave a Reply